The right choice for your situation will depend on a number of factors specific to your finances, your goals, and your needs and challenges to address. But that being said, let’s assume that you’re interested in a cash exercise — and need to know all the details inherent in this option.

Here’s what you should consider.

Why You Might Choose a Cash Exercise of Employee Stock Options

You would likely choose a cash exercise if your goal is to maximize your position in company stock, with the hope that stock price goes up. A cash exercise might also make sense if you want potentially preferential long-term capital gains treatment on further appreciation of the stock.

It sounds like a no-brainer to choose a cash exercise when you consider this tax advantage, but there’s a reason it doesn’t make sense for everyone. If you choose a cash exercise of your stock options, you pay for the cost of the option shares with cash out of pocket.

It will also most likely result in a larger position in company stock as compared to what you would hold if you did a cashless exercise. While a larger holding in one stock can be a good thing, it can present specific risks that you may or may not be in a position to take.

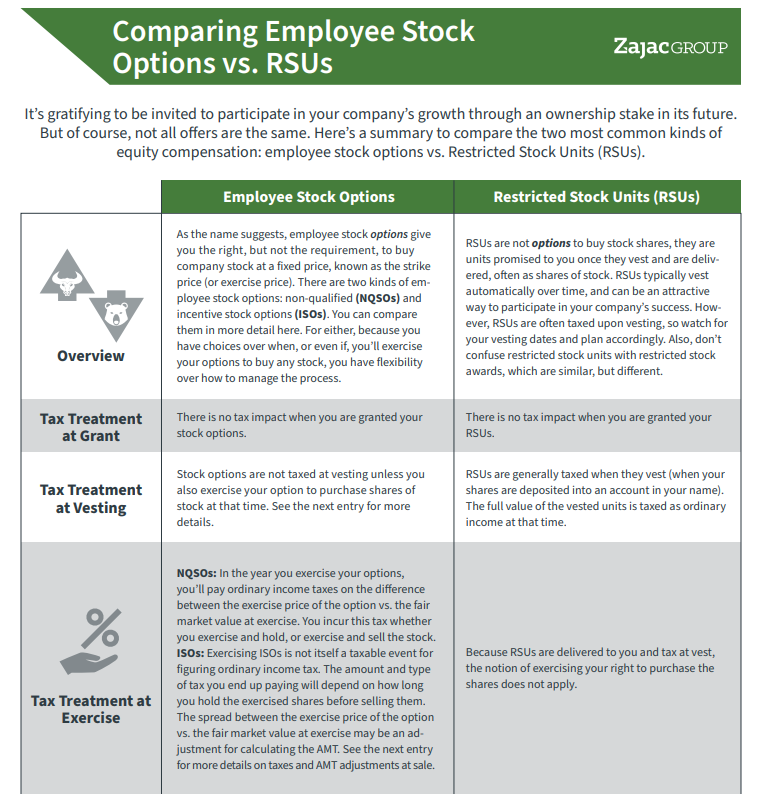

COMPARISON GUIDE

Not All Stock Offers are the Same! Here's a helpful comparison between two of the most common employee stock options.

There are a lot of potential upsides if the stock value rises; you’ll get the reward of a higher account value for assuming single stock risk in this case. But should the stock price drop, you’ll instead be punished for the concentration risk you took via a lower account value.

This risk-and-reward tradeoff is fundamental to all investing decisions. However, all else being equal, the risk you assume may be higher when choosing a cash exercise when compared to the risks presented by a cashless exercise.

To better evaluate if you can handle that risk or not, you should consider the actual cost of a cash exercise.

How to Pay for the Shares of a Cash Exercise of Employee Stock Options

In some scenarios, paying for a cash exercise of your employee stock options can be quite simple. If the cost to exercise is low or if you have cash on hand, you can use cash to pay for the cost of the exercise.

Here’s a quick example to show how you can calculate the cost of a specific cash exercise:

| Number of Shares | Exercise Price | Current Price | Market Value | Value Less Cost |

| 5,000 | $1.00 | $25.00 | $125,000 | $120,000 |

In the above scenario, the cash required to purchase the shares of stock is small. You would only need to spend $5,000:

“Number of Shares” x “Exercise Price” = Cost of Exercise

5,000 x $1.00 = $5,000

Should you choose to use $5,000 to do a cash exercise, you immediately own 5,000 shares valued at $125,000. This is certainly not a bad deal and is easy to do because of the relatively small cash requirement.

(It should be noted that this example does not include the associated taxes due upon exercise. The tax costs will be dependent on the type of shares being issued. Whether you have incentive stock options or non-qualified stock options will impact the outcome here.)

But what happens if you need considerably more than $5,000 to perform your cash exercise? If you don’t have large amounts of cash available you might need to find an alternative funding source.

Let’s continue with our initial example, and now assume the exercise price changed from $1.00 to $20.00 per share. The impact of this change in exercise price substantially increases the cost of a cash exercise:

| Number of Shares | Exercise Price | Current Price | Market Value | Value Less Cost |

| 5,000 | $20.00 | $25.00 | $125,000 | $25,000 |

“Number of Shares” x “Exercise Price” = Cost of Exercise

5,000 x $20.00 = $100,000

While many people may have $5,000 in cash available to spend to perform a cash exercise when the exercise price is $1.00 per share, not as many will have $100,000 in cash (plus the taxes associated with the exercise) to use in this updated example with a higher exercise price.

The issue isn’t just about the cash, either. A bigger question should be asked as well: Would the same person who does have an extra $100,000 lying around want to take this cash cushion and use it to buy just one stock, or is there a better investment option available?

For those who don’t have the cash and wish to buy the stock via a cash exercise, you’re not completely out of luck. You may be able to take the following actions to generate the required cash:

- Sell assets from a brokerage account

- Borrow the money from a bank

- Borrow from a friend/family member

- Borrow using your house (home equity or otherwise)

- Take a loan from a 401(k)

- Use a margin account

As you can see, a number of options exist that could allow for a cash exercise. But if you ask me, none of these are particularly attractive.

That isn’t to say there isn’t a time and place for certain strategies, but all of the options above require you to take on an added level of risk.

Understand the Risks You Might Take to Generate Cash for a Cash Exercise

To better understand these potential risks of trying to use alternative funding sources if you don’t have cash on hand for a cash exercise, let’s keep on with our example.

Assume that you decide to borrow the $100,000 required to perform the exercise from a family member. Immediately following the exercise, you own 5,000 shares of stock at $25.00 per share, for a total value of $125,000.

If you take a snapshot of that scenario as soon as you complete your exercise, you could argue that this is a reasonable position to be in. You own shares worth $125,000 and you owe your family member $100,000, so you make a profit even after repaying your relatively.

As time passes, however, the value of the shares you own will fluctuate up or down. Most people who choose a cash exercise feel optimistic about the chances of the stock price going up — but what if things don’t go according to plan?

Imagine the price goes down by 20%, to $12.50 per share. As the price drops from $25.00 to $12.50 per share, the value of the shares drops from $125,000 to $62,500.

| Number of Shares | Share Price | Market Value | Debt | Net Value |

| 5,000 | $25.00 | $125,000 | $100,000 | $25,000 |

| 5,000 | $12.50 | $62,500 | $100,000 | ($37,500) |

In this unfortunate situation, you still own stock shares — but they’re only worth $62,500, and you owe your family member $100,000. The leverage you used in borrowing money to buy shares left you in the unenviable position of owing more than the stock is worth.

This is an example of the additional risk you can take in trying to come up with alternative funding sources for cash exercises of stock options.

What If You Tried a Cashless Exercise Instead?

What if, instead of borrowing money to perform a cash exercise, you went with a cashless exercise instead? In that case, we could assume you did not take a loan from a family member to pay for the shares. Instead, you would use some of your shares to pay for the others (immediately exercising and selling enough to cover the cost).

Without getting too deep into the details, we can assume you need 3,000 shares to perform a cashless exercise. This means that you are left owning 2,000 shares. Even if the share price falls from $25 to $12.50 here, you’re not in such a bad position:

| Number of Shares | Share Price | Market Value | Debt | Net Value |

| 2,000 | $25.00 | $50,000 | $0.00 | $50,000 |

| 2,000 | $12.50 | $25,000 | $0.00 | $25,000 |

As the share price falls from $25.00 per share to $12.50 per share, the market value drops to $25,000. While this value is smaller than the $62,500 in the cash exercise, the cashless exercise also has no debt. Therefore, your net financial position is better in a cashless exercise than in a cash one.

Of course, there’s the flipside: taking on less risk means less potential reward. Should the stock price appreciate instead of drop, holding fewer shares means your total profit would be less than if you held more shares granted by a cash exercise?

You need to determine what kind of risk-reward tradeoffs make the most sense for you and your specific financial situation.

Is a Cash Exercise a Good Thing or Bad Thing?

A cash exercise will likely lead to owning more company stock than would otherwise be owned by implementing a cashless exercise. As we have illustrated, this concentration leaves you with more risk — but you are also in a position to possibly reap a higher reward.

Again, the right decision on a cash exercise of stock options (versus a cashless one) is a person-to-person and situation-to-situation decision.

Are you someone who is interested in market volatility, concentration risk, and generating wealth through investments? Or are you interested in spreading risk, allocating assets, and paying down debt?

Furthermore, what other assets and income do you have and/or expect, and do you look at your company provided stock as simply another form of compensation?

The combination of these answers may lead to a suitable stock option plan that works for you and your financial goals.

This material is intended for informational/educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax, or legal advice, a solicitation, or a recommendation to buy or sell any security or investment product. Hypothetical examples contained herein are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect, nor attempt to predict, actual results of any investment. The information contained herein is taken from sources believed to be reliable, however accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. Please contact your financial, tax, and legal professionals for more information specific to your situation. Investments are subject to risk, including the loss of principal. Because investment return and principal value fluctuate, shares may be worth more or less than their original value. Some investments are not suitable for all investors, and there is no guarantee that any investing goal will be met. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Talk to your financial advisor before making any investing decisions.

0 Comments