RSUs look straightforward because your options can seem limited, meaning you have fewer decisions to make. But the truth is, you may have several choices around the actions to take next, including how to pay the requisite tax due or if you should retain shares after vesting.

Deciding what to do with restricted stock units may even become more complicated if you throw in a post-IPO lock-up period, an insider black-out period, or the need to consider a 10b5-1 plan.

Your choices may have a significant impact on the rest of your financial life, so you need to understand how to appropriately evaluate potential outcomes and choose a course of action based on what best fits into your overall financial plan.

To make the best possible decisions around how to handle restricted stock units once they vest, there are certain factors and issues to consider.

1 – Vesting Restricted Stock and Paying the Tax Due

Generally speaking, when your restricted stock units vest, you gain full rights and ownership to the value of the units. Often, the value is transferred to you in the form of shares of company stock.

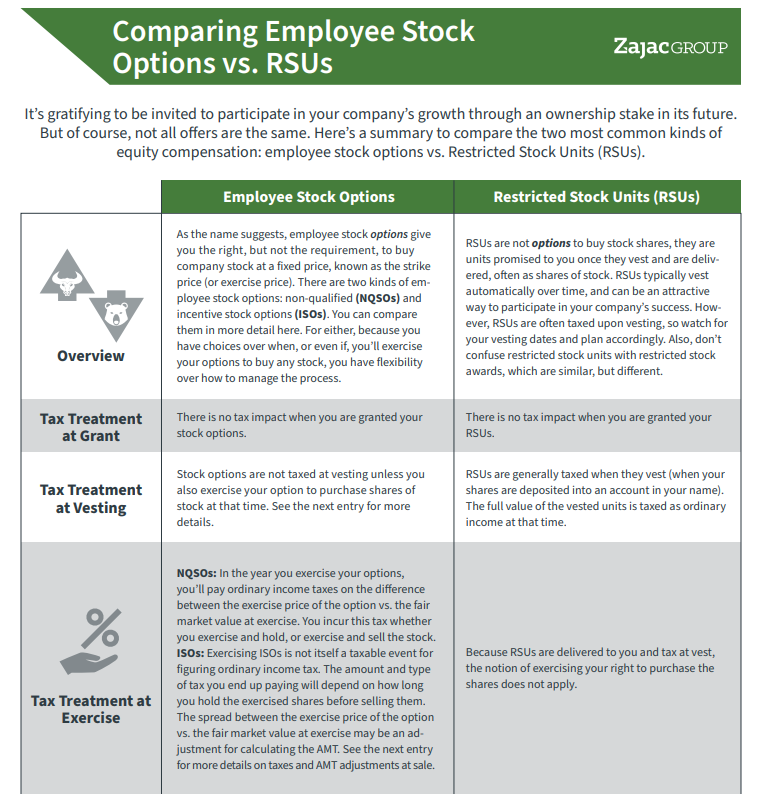

COMPARISON GUIDE

Not All Stock Offers are the Same! Here's a helpful comparison between two of the most common employee stock options.

However, it is possible that your company can settle the value of the units with cash. That means, in lieu of stock shares, you actually receive cash. You should check your plan document to see what might happen in your specific situation and what options you have.

Prior to receiving the value (whether paid as stock or as cash), you will need to settle-up on the tax due. This is because your restricted stock units are often taxed when they vest.

The amount that is taxable to you (as compensation income, which is potentially subject to Social Security and Medicare tax), is equal to:

(Number of Vested Units) x (Fair Market Value of the Stock) = Compensation Income

Let’s assume you have 1,000 restricted stock units that vest when the fair market value of the stock is $50 per share. The amount you will report as taxable income would be:

(Number of Shares = 1,000) x (FMV of the Stock =$50) = $50,000

Your company may withhold some amount of income tax on the $50,000 when the restricted stock vests. Usually, if they do this, it’s at a rate of 22%.

22% is the typical withholding rate for supplemental income, although this could change; this is the current rate for 2019. If you have a higher income, the withholding rate may be as high at 37%.

If we assume a flat 22% supplemental tax rate, we can assume the total tax due when the restricted stock vests is:

(Your Compensation Income) x (Assumed Tax Rate) = Tax Due

So how much tax would you owe if your vested RSUs provided you with $50,000 in taxable income?

(Compensation Income = $50,000) x (Tax Rate = 22%) = $11,000

Again, you may actually owe more tax than our above example because of Social Security, Medicare, and state taxes, if applicable (the above example only illustrates income tax rates).

This is where working with a tax professional can be extremely helpful. With so many variables involved, it could be tough to estimate your tax bill on your own.

2 – How to Cover the Taxes You Owe from Vested RSUs

To cover this income tax need, you could consider some of the following options when your restricted stock units vest:

- Net Exercise – A net exercise allows your employer (or the issuer of the company stock) to withhold the number of unit required to meet the pending tax bill prior to delivering the remainder to you.

- Cashless Exercise – In a cashless exercise, you immediately sell some of all of your shares of restricted stock units. If you choose to sell only enough to cover the tax bill, it is often referred to as a sell-to-cover. If you sell all your vested shares, it is commonly referred to as a same-day sale.

- Cash Exercise – A cash exercise means that you pay your company the amount of cash required to cover the tax bill at the time of exercise. This results in your retaining the maximum number of shares.

Don’t assume that just because your company may automatically withhold 22% to cover taxes, that this is sufficient to meet your total tax need. You may still owe additional tax at the end of the year, pending your specific tax returns.

Let’s assume that your adjusted gross income for the year is in the highest tax bracket of 37%. This may mean that the $50,000 value of your vested restricted stock will be taxed at this rate, not 22%.

If you only paid 22% because that’s what your employer withheld when your restricted stock vested, you might not be off the hook yet. The difference between the two tax brackets, 15%, would potentially be a tax due when you file your return:

Tax Withheld at Vest (22%) – $11,000

Tax Due per AGI – (37%) – $18,500

Additional Tax Due (potentially) – $7,500

Know your tax situation so you can plan for the tax due if any. In fact, knowing a tax may be due may be a reason to make an estimated tax payment in the quarter the restricted stocks units vest.

Again, it may make sense to work with a CPA or an advisor who can help you work through the numbers. Each tax situation is different, and hypothetical examples like the above are only used to illustrate a point, not make a recommendation.

3 – Keep Your Restricted Stock Shares or Sell Them?

When the dust settles from vesting, paying tax, and obtaining your share ownership, you need to decide whether to keep the shares or sell them.

If you keep your shares, you will be subject to the risk-reward trade-off of owning a single stock position. A single stock position is often considered more volatile than a portfolio of stocks, meaning you may be more likely to see a greater level of volatility.

If you choose to keep the shares, you may want to consider how much of your net worth is already allocated to this single stock position. One simple rule of thumb suggests that an appropriate allocation to one stock is 10-15% of your net worth.

If you find yourself with a greater percentage than mentioned, it may warrant a longer conversation about your financial planning goals, objectives, and risk tolerance.

If you decide to sell your shares, you will be subject to tax rules for selling an investment — which means you need to be aware of short-term and long-term holding periods and how each could affect you.

A holding period is a time between when the shares were purchased and when the shares were sold. A short-term capital gain (or loss) is anything that is sold prior to being held for 1 year, and a long-term capital gain (or loss) applies to anything that has been held for one year or more.

Your holding period for the restricted stock shares typically begins on the date the shares vested, and the holding period helps determine what tax may be due.

When you sell your restricted stock shares, you may report income based on short-term capital gains tax rates and/or long-term capital gains tax rates. Short term gains are typically taxed at ordinary income tax rates. Long term gains are subject to preferential long-term rates.

The gain or loss is the difference between the cost basis of the stock (purchase price) and the sale price of the stock. The cost basis for restricted stock is typically equal to the value of the shares on the vesting date.

Continuing our example where the restricted stock had a cost basis of $50 per share, we can see the impact of the different holding periods on taxes owed:

| Shares | Purchase Price | Sale Price | Tax Rate (assumed) | Tax Due | |

| Short Term | 1,000 | $50 | $90 | 37% | $14,800 |

| Long Term | 1,000 | $50 | $90 | 20% | $8,000 |

4 – A Sidebar for the 83(b) Election of Restricted Stock Awards

The tax rules above cover both restricted stock units and restricted stock awards when they vest. However, if you have restricted stock awards (not restricted stock units), you may want to consider an 83(b) election when the grant is awarded.

If you choose an 83(b) election, you choose to be taxed on the value of your unvested restricted stock when it is granted, not when it vests.

The hope for those who elect 83(b) is that the total value of the award is lower at grant than it is when it vests. If this plays out to be true, then you will have needed to pay less in income tax than had you not elected 83(b).

The risk is twofold. One, you are paying tax on something you don’t yet own. If you forfeit the shares prior to the vesting, you will have paid tax on something that you never owned.

A second risk is that the award decreases in value from the time the award is granted to the time it vests In this situation, you will have likely paid more tax than you would have had you waited.

The rules for an 83(b) election can be complicated. The same goes for properly evaluating the risk/reward tradeoff of this decision. If you are considering this as part of your strategy, you may want to speak with a professional.

5 – What Else You May Need to Consider for Your Restricted Stock

There often isn’t much you can do in terms of controlling when your restricted stock vests and the value of those units. But that doesn’t mean you should turn a blind eye to your restricted stock units.

You may be able to use your restricted stock units to plan for other financial planning needs.

For example, if you require a cash need for a new home, a college expense, or a vacation, you may be able to plan a cashless exercise of all your shares, netting the proceeds as cash that can be used as funding for other goals. You may also be able to use vested restricted stock to fund your retirement plan.

In a more complicated example, you may want to evaluate a decision to keep/sell your vested restricted stock shares based on what other types of equity compensation you have now or had in the past.

If you have previously-vested restricted stock shares that have reached long-term capital gain status, you may be able to use those shares to exercise a stock swap at exercise. (This is subject to the rules laid out in your plan document). The net result of a stock swap is often less cash out of pocket.

From a compliance standpoint, you might need to consider whether or not you can sell the shares at all. Special rules may exist for companies that went through a recent IPO that restrict the sale of your securities.

Other times, those with inside information may be locked out of selling during certain periods. Or, if you are an executive, you may find yourself tied to a 10b5-1 plan.

Regardless of your situation, restricted stock units may offer you an opportunity to take the share value once vested and redirect it into something other than company stock. Make sure you do the appropriate planning to make the best choices with this opportunity to further your progress toward your goals and financial success.

This material is intended for informational/educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax, or legal advice, a solicitation, or a recommendation to buy or sell any security or investment product. Hypothetical examples contained herein are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect, nor attempt to predict, actual results of any investment. The information contained herein is taken from sources believed to be reliable, however accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. Please contact your financial, tax, and legal professionals for more information specific to your situation. Investments are subject to risk, including the loss of principal. Because investment return and principal value fluctuate, shares may be worth more or less than their original value. Some investments are not suitable for all investors, and there is no guarantee that any investing goal will be met. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Talk to your financial advisor before making any investing decisions.

In the table in section 3, wouldn’t the tax due in the long term row be $8,000? I am assuming the math to calculate the tax is ((sale price – purchase price) * number of shares) * tax rate. So I think it would be ((90-50) * 1000) * .2 = 8,000?

Perhaps I am screwing up the math somewhere though

Yes – you are correct! Updated

Thanks!